Gay Community or Civil Rights Community?

. . . . The 1975 Third National Conference

I billeted with David Garmaise. The national conference in Ottawa in 1975 was billed as The National Gay Rights Conference, and was relentlessly oriented towards civil rights issues. There was a sub-conference taking place at the same time to deal with setting up the National Gay Rights Coalition. This should have left a little room at the main event for other things besides rights but that wasn't the case.

Civil rights had always been one of the hooks on which gay lib had hung its hat. There was nothing new there. What was different was the attempt to marginalize everything else, to essay a movement which had only one face, one way of speaking, one thing to speak about. That left a lasting and bitter taste.

The conference itself had many interesting discussions and was certainly of value as a morale booster. But at times it was conducted like some sort of mock legislative assembly, factions running around with resolutions they wanted passed, as interested in counting votes as anything else.

This is all by the way. Bring gay activists from coast to coast together and certainly they'll have useful things to say. The dialogue will be good no matter that you force it to take place within the procrustean framework laid out in Ottawa in 1975. But I felt uneasy. We were so busy performing to a straight world, arranging the face we would present to them, presenting the grievances we wanted adjusted, that at times it seemed we were only peripherally addressing ourselves and the needs of the people in the communities we came from. Of course this has often partly been the result of being at the mercy of the straight media, having to play to them. Being able to reach our own people only indirectly, through those media, has always been a major frustration. But part of the problem is also that it has often simply been an easier and clearer exercise to confront a straight world than to deal with a gay one.

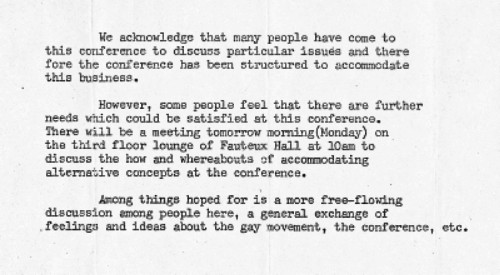

I didn't feel comfortable being overly critical. But by Sunday, after talking it over, Danny Gerrard (I thnk it was Danny) and I approached the organizers. We wanted a room for a workshop at which we could try for a less structured conversation than had been allowed up to this point. Although they had ostensibly left open the possibility of such sessions happening, they were very grudging. They didn't see the need of anything beyond what had been scheduled. We tugged our forelocks and in the workshop notice, bent over backwards not to appear critical of the conference.

The next morning before we got started, Ron Dayman, by then with Gays of Ottawa and one of the main planners of the conference, came by. I went over to assure him again that we were not trying to be obstructive. But he seemed personally affronted by the whole idea, gave me a look of hostility, total disgust. What can you say?

10 AM on the Monday we attracted about fifteen people. The problem was we weren't offering anything ready-made, weren't proposing a particular topic of discussion so much as trying to see what was on other people's minds. As I've mentioned, it was mostly a feeling of uneasiness that motivated us.

Clearly gay rights concerns, the focus of the Ottawa conference, have been invaluable in forcing public discussion of many issues involving our relationship with a straight society. The problem lies in allowing the parameters of our message to be determined by these issues. This conference visualized us as a civil rights community rather than a gay community.

In the Canadian context the gay rights approach to gay lib had two major motivations. First, the concentration on rights was supposedly a way of uniting philosophically divergent gay organizations around a common goal. In a sense the way the 1975 conference was structured was a response to this thought and to the formulations and directions issued by previous gatherings. (This had also been a prominent line of reasoning at the founding CGRO, Coalition For Gay Rights In Ontario, conference in Toronto earlier in the year.) Tactically this also kept us from becoming embroiled in issues that were not central to gay concerns. Nevertheless there is such a thing as overkill, a particular strategic posture was being allowed to overwhelm everything else.

As the other driving and central motivation in all of this, the gay rights formula was a marketable way of presenting the gay movement to the straight media.

Of course any direction the gay movement took was also determined to a great extent simply by the temperament of the people involved and that's, I think, a very important factor here.

But while laws certainly needed changing, our concern had also always been directed towards the formation and effects of a whole range of social attitudes. Gayness, and what it meant to ourselves and the rest of the world, was part of our message.

Among other things, we were suggesting to gay people the idea of gay community, though defining that remains a difficult task. In one way it probably meant a sense of allegiance that would give us the strength to reshape our circumstances on our own terms. This included a committment to the actual range of our needs as a community, a desire to address what we could.

In a larger sense I think we were saying if we looked we would discover within each other common bonds, not of oppression but of liberation. Gayness, gay lives, gay sexuality, these things themselves (and not simply the perspective gained by being marginalized by society) could be sources of insight, a resource both for ourselves and the rest of the world.

Gay experience and gayness extend well beyond their clash with heterosexual society. We are a diverse people. There are other facets of our existence and other things besides the legalities of our situation that need to be addressed. That isn't to downplay the seriousness of those legalities. The point is, a gay rights strategy that isn't accompanied by an ongoing discussion of other aspects of gay lives and life, including sexuality, raises as many questions as it answers.

This conference seemed to be attempting the eradication of the vestiges of such considerations from the gay movement, the imposition of a set of goals and a viewpoint that placed these things firmly outside the purview of the movement. Certainly the community would have other concerns that were legitimate and should be recognized. But insofar as that community was concerned the aim of an organized gay movement itself should be strictly the delivery of equal rights. All else was to be seen in that light.

There was a certain kind of political respectability that would come with the formulation of gay aspirations into a civil rights movement. In embracing that formulation so wholeheartedly it almost felt as if the gay movement was turning away from gay people. That may be exaggeration but the central focus was no longer on gay people themselves but indiscriminately on transgressions against us. While for instance I didn't think the military should be allowed to discriminate, I also didn't see that it should be of more pressing concern to the gay movement than the development of community infrastructure or than the more complete exploration of some of the implications of gay sexuality.

So here we were in 1975 and the suggestions of this conference envisioned the gay movement as not much more than a political lobby. Such was the neglect of and even hostility to a more comprehensive vision that there was little in the way of ideas that people were prepared to go forward with at that Monday morning workshop. The only spark that struck was a general complaint of a lack of contact on a personal level at the conference. Eventually we adjourned to the lawn outside to play games and throw frisbees, try to find some other way of interacting. This disappointing failure of a simple attempt at unregimented dialogue, the inability on all our parts to know how to step back and look at ourselves, says much about the state and staleness of the movement in 1975.

One thing does lead to another though. And perhaps expresses what words can't. Once we were out in the fresh air it was decided we wanted to go downtown en masse. There was a march planned for later but it seemed guaranteed to have little contact with anyone but the media. While there were reasons for wanting attention from that corner there were also legitimate desires both to have our presence felt in some way by the city itself, and also to be something other than simply volunteer performers at a pseudo event.

Banners were rounded up and word was circulated. Conference organizers were against it, worried the later performance for the press would be usurped. But the idea quickly gained favour elsewhere and they asked only that we hold off until noon so as not to drain off the workshops. At twelve o'clock joined by about half the conference we decamped and sang, danced, chanted, hugged and kissed our way down to central Ottawa and through the street mall there, generally having a good time.

One more piece of street theatre may not add up to much but it was an emotional expression of something that was lacking in the gay movement by this time, something that has yet to be satisfactorily articulated. Partly it had to do not with celebrating ourselves but perhaps with taking joy in ourselves, a matter of attitude; partly it was a rambunctious gayness that belied the idea of an orderly gay movement.

As usual there are details about which I'm uncertain but this is my best recall. There were two marches that day. The climax of this first, unofficial one was a spontaneous and inspired thing, a moment which seemed somehow to speak to our aspirations, lift them beyond the mundane of placards and banners. We arrived on Parliament Hill unannounced. A couple of security people had a quick look, decided this was no threat to the nation and stood away. There was no staging, no speech given, we lay down our signs and banners, simply joined hands in a circle in front of Parliament and danced in a large revolving wheel. There were few spectators, no chants, it was a moment that belonged to us alone. And then, our dance done, we picked up our placards and melted away.

This particular memory is the simplest and most beautiful of any I have of the gay movement. And what made it that I have no idea. We'd touched down in another universe for a few seconds and everything that troubled us had been left so far behind it wasn't even a memory. Surreal and somehow magic, there was only us and this different world.

The attempt to recreate this later, at the end of the second, official, march was a failure. Everyone joined hands in an immense circle once again and once again danced. But a moment so ephemeral it can't even be described properly can't be summoned twice.

At the conference dance following the official march we all stopped to watch the national news and its coverage of that march. There we were, receiving our few seconds of affirmation before the country. For five minutes afterwards the packed hall rocked with the sound of a couple of hundred people as they chanted in unison at the tops of their voices "gay rights now!" It was a powerful feeling, spoke both of our exhiliration and to the possibilities that underlay the idea of gay community. I believed in both gay rights and gay community, and found all this moving just as others did.

It was on the train home from this conference that the subject of starting the Toronto Area Gays phoneline was first broached. This occupied my time from 1975 through to 1980, and Charlie's for considerably longer. It seemed, for myself, a preferable expenditure of energy, more in keeping with my own inclinations, than being so totally focussed on the opinions of straight society and its politicians and high priests. As it was, I thought the success of any civil rights campaign was measured more by its ability to reach and influence gay people, than by its effect on straight opinion. I'm aware of the power of the latter and the problems this causes but I felt the more our own opinion of ourselves and of our lot in life changed, then the more momentum and strength we would gather and the less likely gay people would be to accept half-measures and paternalistic semi-rights; and in consequence the more able we would be to bring about the changes we wanted. This seems to me as valid an interpretation as any, of what has been happening since then.

Of course the unfortunate paradox, as noted earlier, is that it was from straight media that most gay people took their lead, and only through these avenues that the vast majority of them could be reached. This required us to both cater to the straight media's appetite for the civil rights angle, for certain kinds of news, and also to dispute and change its homophobic attitudes. Essentially though, it was a gay audience we were playing to.

I suppose I'm implying a fine line here. On the one hand, challenges to straight institutions and to laws, and the publicity these battles attracted, were a vital means of reaching out to more gay people, of getting a strong gay viewpoint out to them, of chipping away at the invisibility and the silence. That these activities prepared a path, softened up straight attitudes for future challenges didn't hurt either, but that was secondary.

On the other hand if the particular laws and rules of these institutions and of society became the overriding concern of the gay movement to the degree it's the only leg we had to stand on, then our agenda became even more essentially a reactive one. The final result of our own tactics would be to limit anything we had to say about gay life and life in general, and about gay sexuality and all sexuality, to a discussion of civil rights. The shape of the gay movement would end up being determined by the needs of the straight media.

As for civil rights themselves, we wanted the protection of the rules rather than being shut out by them. Well that's understandable. But this put us not much further ahead in understanding the compatibility of those rules with gay lives and gay life. We found ourselves with no way of discussing whether within different sectors it was regulatory or structural changes which were needed to accomodate us because we had developed so little understanding of gay lives, and the interaction of gay sexuality with those lives.

Whatever their virtues as a strategy, civil rights did not heal the hurt or deal with the devastation, and wouldn't by themselves prevent these things in the future. Most of all we needed to work out, and make accessible to a gay constituency, some view of ourselves as gay people that didn't depend on what any legislature or parliament had to say about us. We continued to give straight society the power to define us so long as the only way we outlined gay existence was in terms of homophobia and legal status. No matter how things shifted we would always be controlled by society's attitudes towards us if our only developed means of thinking about gay lives was in relationship to those attitudes. That is what bothered me in 1975, and what bothers me still.

These days, I suppose it's a case of taking what we can get and trusting none of it. But while we need a basic level of civil rights to advance in other ways, it's also true these things all feed off one another. Not by any means am I suggesting we ever ignore rights issues, they provide a hard, good, and necessary edge. What I am saying is that they are only one part of a more complete affirmation of gay experience itself, and that reducing the dialogue of the gay movement and its message to gay people to only a demand for rights, to the lowest common denominator, is an abdication.

The small announcement we made for our workshop