FAMILY, RELIGION, HIGH SCHOOL

All of this is very distant to me. I've tried to recall my relationship with my parents in enough detail to make sense of how it played out; and in a way that is fair to them, that at least tries to understand them. All in all my childhood was pretty humdrum, certainly tedious to write about. Meant as a historical artifact my congratulations to anyone who has the patience to read through this.

PARENTS

FATHER:

My father, age 19 or 20, with his motorcycle in Germany.

Twenty when he left Germany for Canada in 1930, my dad was a combination of smart and tough. While only 5'9" he was physically intimidating and easily angered. Few people who crossed him got away with it. A 1930s car accident left him with a scar between his upper lip and nose that fit in well with that aspect of his personality. Though a pipe fitter by trade, he worked as a miner in northern Ontario to put himself through college, getting a degree in civil engineering just before the start of WW II. A bad time for a German immigrant but he finally managed to land an engineering job and by the end of the war had his own consulting business. Under the War Measures Act my father in 1939 was required as a German-Canadian to register with and report regularly to the police. Once he had calculated his value to the war effort as an engineer had increased enough he refused to report any longer. (In a bit of deja vu, when the War Measures Act again poked up its head during the Quebec crisis of 1970 someone reported my father's hunting rifles to the Quebec Provincial Police and they visited my parents' home. I can't remember whether or not my my mother said they took the rifles.)

For the first six years of my life he was away on work sites for months at a time. This vanishing act was broken with visits home, a week here, a week there. When he arrived back I'd hide from the strange interloper, not quite sure what he was doing in my house. That's the short version. In truth, though born in Montreal my first year was spent with my parents and brothers in the northern Ontario mill town of Red Rock. In later years we'd occasionally be with my father in twos or threes for short summer visits in mill towns, lumber camps and construction sites anywhere from Red Rock in northwest Ontario to Sept-Iles in far east Quebec.

As he prospered the family moved from a tiny winterized cottage with no running water to a slightly larger one with indoor plumbing to a place actually intended for year round occupancy and finally to a large brick and stone house he built with his own hands in 1951-2. Over the next decade he took time between engineering contracts to build several more houses intended as rentals, his sons providing casual labour as available and needed. Possibly this is where part of his estimation of me originated. I graduated from straightening kegs of used nails, to hammering subfloors, to eventually being up on the roof nailing down shingles. But I was always a klutz, more than once falling between joists and ending up hanging by my armpits. A hammer was the only thing I was ever trusted with. A father who could build those houses, design paper mills, patent engineering techniques, fly a plane, supply our winters with endless venison and moose, and much else -- if he'd been less intimidating I might have learned something from him. On the other hand, given my own limitations, maybe not.

I was always wary in his impatient and judgmental presence. No words need be spoken to know how he felt about anything and only when he was out of town could the rest of us begin to let down our guard. The closer any scheduled return the quieter the house became. For my brothers, earlier in the parenting cycle, it had been harder, with my mother less able to protect them. That resulted in a certain amount of resentment on their part, they'd comment from time to time on how much easier I had it. But brotherhood, in any case, wasn't a big thing when we were children, for the most part my brothers and I led separate lives. (Though both died of natural causes neither lived past their sixties, unusual for my family.)

With me, if I was obedient, kept out of trouble, acted in some facsimile of how a boy was expected to act, my father was content to leave things be. That more or less worked until I was ten or eleven. Nevertheless it had always been a shaky relationship (in our view of one another, me the overly delicate china shop and him the bull) and the more we were in each other's company the more unhappy we were with the situation. One scene from my early teen years --- he's standing over me, plate of food in hand, threatening to close the distance to my face. I'm staring at him, he's staring at me, my mother is staring at us both. A long few seconds of silence. Then he puts the plate down and with a few nasty words walks away, presumably having learned from how he treated his two older sons that this was a road that led nowhere but away from him.

My oldest brother regarded him at best with an ambivalence that veered towards hatred. My middle brother, though he was the smartest and most successful of us, could never get that full approval he craved. No one could. My mother said my father was hurt by the way his sons felt about him and I have no trouble believing it. Hurt happened in all directions and, undoubtedly a lot of it was unintentional. Some of it too was simply the way boys were once raised. In the thirty-three years before my birth there had been two world wars and the Great Depression. My father would have said he was trying to make sure his sons would have the tough hide necessary to survive in such a world. This attitude was to an extent even official policy at the time, army cadets still being compulsory at my school in the 1950s. Fortunately I had trouble telling my left from my right and my cadet career lasted only one day thanks to the havoc I created in parade drills.

In trying to understand my father I've had to consider his own childhood: a young boy growing up in a small German village near the French border during WW I and its aftermath. After his mother's death in his teenage years, his father quickly remarried. Resentful, angry he broke with the man, refusing to reconcile until the mid 1950s. His father in turn had parted from his own parents and culture as a young adult, had left the Veneto region for Germany in the company of his older brother, presumably out of poverty. It's a familiar story of uprooting and emigration, but with this repeated breaking away what is lost, not passed on about being an adult, a father? And with life requiring bloody-mindedness in order to survive how do you learn to leash that mindset in ? This isn't meant to offer excuses for my father so much as an attempt to make out how he ended up the kind of parent he did.

As a young boy with no understanding of these things, all I knew was to tread carefully. Given how both homophobic and upset with anything considered feminine in a male my father was, it required intense self-censorship to be around him. Aha, training in a self-consciousness at the root of queerdom's gilded artifice ! Good luck with that. I was simply stuck with the self-consciousness and the awkwardness that accumulates around it. All my life it played hide and seek, jumping out to paralyze me at the most inopportune moments. A shy, fearful child, blushing became a permanent torment, first appearing during a small and smugly self-satisfied public humiliation by my father when I was eight or nine. My developing interest in male bodies had begun to be clear to me, but with it came this sudden warning about letting that interest show. While in the future I might be bold, even impervious, in some areas, here at a young age was a very particular and newly discovered tender point.

Even without his homophobia, being around my dad always made me feel I didn't quite measure up. That he had reservations about most people was hardly consolation. So I preferred as much distance between us as possible. Which he understood, and which gave him opportunity to pull rank. No matter how unobtrusive the attempt, in those last years at home I was not allowed to leave any room we found ourselves together in until he said so. After leaving home I did visit often in the first year (it was after all where my mother lived) and less frequently until the end of 1970. The first time my father spoke less than politely to me after my move out I got up and left not only the room but the house, caught the train back to Montreal. That upset my mother and out of respect for her feelings it became the last time he spoke that way in my presence, if hardly the last time he spoke of me with disdain. Power had not shifted but once I no longer lived under his roof I could change the way the game was played. That made it possible for us to get through my visits in the 1960s with a modicum of politeness towards each other.

By the 1970's he finally understood I was gay, as opposed to merely suspecting. From then on he held my sexuality against my mother for supposedly coddling me when I was young, for letting me drink milk as a child, for any of a dozen reasons. It became one more thing she had to deal with. When I phoned to talk with her and he answered he could no longer bring himself to be civil and I didn't see him from 1970 until his dying days. But there was a time, twelve years before his death, when he phoned in distress and I did what I could without resentment. Having never witnessed my father cry before, all I could feel was empathy. He seemed to appreciate both my help and that his understanding of our relationship and who I was, was more complicated than he'd allowed himself to believe.

After that we could at least manage a few seconds of phone conversation before he passed me along to my mother. This change allowed us to be in each other's presence once more at the very end. The chasm between us, though, was too wide and too deep to ever really bridge. Even on his deathbed, where I bathed and fed and attended him in the last weeks of his life, he was who he was just as I am who I am. At that point in 1994 it had been 24 years since we'd laid eyes on each other. Given it would never have been possible for us to really get along there's no regret on my part. But I did cry when he died.

And here just a glimpse, because glimpses were all I ever got, of that other father. Over the years each of his three sons had one trip alone with him to a worksite. For my turn the two of us flew TCA to Fort William, saw a ship launched in Port Arthur, then went on to Red Rock where he was doing some extra work on the mill. I must have been six or seven, though my mother suggested I was older. In any case on this trip he was kind and gentle, and there were no angry words or judgmental glances. During the week we were there I had no fear of him. Why he had such difficulty letting that person to the fore is a mystery. This was one of the few times it was more than a shadow you sometimes sensed.

Trying to do him justice has been a major roadblock in writing about my parents. An incredibly hard working person, there was much about his life worthy of admiration. Despite his difficult and belittling ways, to his credit he attempted to be a just man as he understood such a thing and there were times when he did the best he could to offer respect. He came to regret much in how he had raised his sons and my mother says he did love them. Perhaps it would have been simpler if I couldn't see him from more than one angle. Eventually though, you do take some measure of it all. It wore you away as a kid dealing with him in tandem with the homophobic culture of the times, parts of you were lost that would never return. I have no hesitation in saying I wish I'd been able to get away sooner. So while he was not a bad man, whether he should ever have been a parent, or even a husband, is another question. Certainly he should never have been any gay child's parent. But if I cannot exactly say I loved him there remains this --- he was my father.

------------------------------------------------

MOTHER:

My mother I did love intensely as a child. That too comes with its problems when you begin to cross from who everyone wants you to be to who you are. I can still see her standing alone on our porch, watching as I reached the corner of our street the day I left. I waved to her, she waved to me. Though I'd visit for a few years, that part of my life ended as I turned away.

My mother at 22 in Toronto.

At 24 in Geraldton, ON, shortly after her 1939 marriage. Both my and Charlie's parents were living in the area at this time and he was born in Geraldton a little more than a year later. But our parents never met and mine were gone by then.

With my mum especially, it helps to know her background. (Though we always spelled it "Mom", we pronounced it "mum" and I'm talking with her in my head as I write.) Her own mother was the daughter of Irish immigrants and her father was a Chinese immigrant who spent his life working in Toronto's Chinese laundries. Their marriage in 1903 was not something that was ever going to be viewed with societal approval and as laws and attitudes became even more restrictive it didn't become any easier. (With few Chinese women in North America, most Chinese men who married in 19th and early 20th century Canada and USA found their wives among the Irish and Indigenous, considered particularly low status women.) My grandfather and all his children including my mother were forced to register under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923 (formally known as (the Chinese Immigration Act) or face fines, jail, and/or deportation. The 1924 registration paper for my mother includes a photo of her as an unsmiling nine year old and, among other things, notation of physical identifying marks.

After the passage of the Act the Chinese laundry my grandparents ran in the family home on Davenport Rd. was closed and the family moved. My grandfather then worked at another laundry, sleeping there and only returning home on weekends, while my grandmother took work cleaning houses and as a rag picker in a local factory. The family name was changed and eventually my grandmother began listing herself as a widow on censuses. The parents of some of my motherís friends refused to let them play with her any longer.

With six children in the family needing to be fed, clothed, housed, and educated, her own parents had more than enough on their plate without the added sting of a racism they'd had to deal with from the beginning. There was little left for extras, Christmas for instance usually depended on the Star Santa Claus Fund. At twelve my mother developed pleurisy and spent a year in hospital having a lung drained daily through a hole in her back. Once recovered she went on to do well academically in high school, develop a new set of friends, even manage at 5'2" to somehow play on the basketball team. And the family did claw its way out of poverty.

She was able to escape prejudice in future years because there wasn't much about her appearance that hinted at her racial background but the memory of these years hovered for the rest of her life. One of her brothers, who looked considerably more Chinese, referred to it all as a tempest in a teacup and barrelled through to a medical degree. Illustrating again that when it comes to history much depends on who's doing the telling.

However much her experience of bigotry had affected her it didn't keep her from marrying a man with a heavy German accent at the beginning of WW ll: not the best career move in still very British, very colonial English Canada. Given her own history, when it came to the minor childhood problems of her children there was sympathy but it came with the expectation we'd try to pull ourselves together.

My parents met at a dance at the Harmonie German Club, 519 Church St. in Toronto. The building later became the city's gay community centre.

While she strongly believed in people minding their own business she was a sociable woman. During my childhood she was a member of bowling teams, bridge clubs, had good friends among the neighbourhood women. What she did mostly alone was walk, making time in afternoons for a long, brisk, take-no-prisoners jaunt. People knew her by sight as the woman who walks. Her habit continued long after my father died, right up to the point she needed a wheelchair. Without elaboration she told me these walks were what had kept her sane through the years, she wouldn't have got through without them. For the most part with my mother you were expected to read between the lines, draw your own conclusions. You can figure it out, you're perceptive, she'd sometimes say. Because I was a good listener people thought I understood it all.

Her caution about saying too much was hard to get past and much is obscured when it comes to her relationship with my father. I search among the details but can you ever fully know your parents ? My middle brother said one time when we were young they were having a disagreement and my father went to the cupboard, filled a suitcase with her clothes and put it on the porch - it was his way or she could leave. What my brother didn't say and probably was too young to know was how they resolved that conflict. Though they hid most of it from us, much of their life together was troubled with his dissatisfactions and perfectionist ways.

His occasional small disparagements of her in front of other people were of course much resented by her children even if she showed no reaction herself. In one of her other old age confessions she said her mother was shocked when she visited, asked why she allowed him to behave like that. Long after he died I asked my mother whether she'd loved him and she said yes, but again didn't elaborate in any way. She did admit in a letter that before the 1960s they hadn't got along well. But also only once did she ever make a direct complaint to me about an action of his, and never did I hear her raise her voice to anyone. While acknowledging he could be a problem she also disliked anyone speaking against him, and in their disagreements my father didn't always get his way.

Later on their life together became more peaceful and happy. But until my father's death there would be that calculation and trepidation in my mother's choices, over what his reaction would be. After he'd chosen to die rather than remain bedridden, she, against her better judgment, said something about one of my brothers that upset him. As a result in the weeks that remained he refused to speak to her or anyone else, though he would hold her hand to show his love. And that's the way he went out. Except for one last shout as his life ended.

Probably what my mom had eventually come to want most in family life was for the turmoil to end. Before my father's death, her sons moving on to their own lives had, to a degree, allowed that to happen. When she gave birth to another child at age forty-seven my parents took that as a chance to start over. (Though I was fond of her as a child I have absolutely no tolerance for the adult version of this sibling.) My dad though happy was embarrassed enough by my mother's pregnancy he refused to be seen with her through most of it.

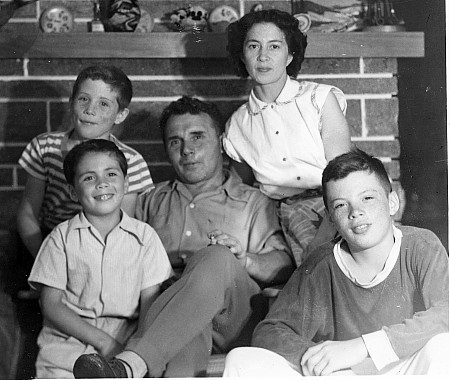

I'm probably seven or eight in this photo. My middle brother, behind me, inherited his red hair from my Toronto grandmother. Hers turned white more or less overnight in her early thirties.

------------------------------------------------

LATER:

While it might be left at that, there remains my own relationship with my mother to decipher. Over the years I kept in contact with letters, phone calls, cards. Very occasionally, years in between, we'd meet in neutral territory. She visited Charlie and me a couple of times in the 1980's once she was sure it wouldn't anger my father, even met Charlie's family, curious about their acceptance of me. After my dad died it all became much easier and we saw her often. People and circumstances change and relationships don't survive intact with the kind of long absences that mine with her included, but we managed.

The correspondence we kept up in the meantime was particularly difficult because so innocuous. Writing letters required me to allow that emotional turbulence of childhood back into my life. In the process my parents would start to inhabit my dreams again. A little too close for comfort, that. My sexuality was so much a part of who I was, pivotal to how my life developed. My father couldn't tolerate it, would probably never be able to deal with it. My mother acknowledged and accepted it, but in her own mind it was a flaw, something that had gone wrong. If there was nothing to be done then as far as possible it was best ignored. The person I was to her sometimes felt her substitute for who I actually was.

But she always welcomed Charlie with warmth and respect, accepted him and our relationship. It was a fuller understanding of that relationship and his and my part of the world that took longer. Being a loving mother she wouldn't say such a thing but there remained almost to the end difficulty in seeing an equivalence in value of that relationship with the hetero ones of her married children. (Probably a Catholic hiccup.)

It became a matter of slowly bringing her along, trying to let her see a bit more of life at the other end of the telescope. She believed in "expert" opinion and it was a long trek getting her over her feelings of guilt about my sexual orientation, which her readings interpreted as caused by overprotectiveness on her part. And by my father's not being present enough in my life --- as though a gay child could have survived being exposed to him at any greater length.

The times we did see each other before my father's death we managed to speak fairly openly, if not at length, about these things. But usually, given that continued reluctance on her part to speak freely, you had to filter through her words for any message. She definitely preferred people communicate in the same manner as much as possible. That way anything she wanted to avoid or couldn't respond to without causing problems, she could let sail by unacknowledged: choose your battles her strategy in life.

In any case accusations and recriminations weren't of interest to either of us. Daily life wasn't censored from my letters but sometimes I'd also attempt to be straightforward with my feelings, risk some reference. Putting the letter aside a few days to give a bit of distance, I'd reread it. Then of course it would have to be rewritten, leaving it as it was would simply push her away. And so it would go, rewrite a second time, a third time, until there was truly nothing left but a cheery message. Which I'd known all along was what she wanted. It was prolonged, difficult, frankly a repeated source of much pain and sometimes it took months to finish. When she died I got most of my letters back, a match to the ones I'd held onto from her. Those of mine from the 1970s, when my father's animosity was at its peak, she'd destroyed for fear he might read them.

Reading the remaining ones now and knowing what I actually felt at the time they were written makes me wonder how I persevered. It would have been so much easier not to write at all, but then what connection with my family would be left? I wanted at least to have tried my best. Even in this though there is some qualification. On my side, much as I loved my mother, she brought with her the weight of the life I'd escaped, its assumptions and expectations, its particular mindset. On her side I was a source of problems between her and her husband. As both of us tried to keep the thread from breaking there were times when it wasn't only me who seemed to find communication a strain.

Ultimately what seemed most apparent about my family, was the misconceptions we had about each other until the end. That makes it difficult to put any one thing down and say see, that's what it was like. There was often something else in the background that qualified everything. It was never a terrain easy to navigate, in childhood impossible. I'm not sure if time gives perspective or just allows us to forget, in any case I came to accept that parents were only human like the rest of us, and formed like us from what came before. Nevertheless it was also crystal clear why I'd had to get away from mine and why I would never be comfortable around my father. My parents gifts to me were a kind of resilience and obstinacy, an education in bobbing and weaving, and a certain amount of damage. That last of course was par for the course --- Larkin had it right. There were undoubtedly also occasions when the damage flowed in the other direction.

And there you have it: family. I'm not in love with the ritual self-celebrations of the institution.

------------------------------------------------

ALL THOSE OTHER THINGS OF CHILDHOOD:

My childhood memories include many things beyond my family of course. Among these: giant steam locomotives that pulled into the local station several times a day; fields of butterflies in numbers unlike any now; the boy floating on his back, erection in the air, who tried to entice the girl I was with as we swam in a local creek --- when he came sniffing around later she shot him in the foot with a BB gun and sent him limping on his way.

Rather than go through the whole catalogue, here's my particular affinity for old ladies as stand in for it all.

Ella Mae and Alice MacIntosh, sisters in their seventies, lived a couple of miles from me, occasionally rented a room to suitable persons for extra income. Visiting by myself as a boy, doted on, I'd sit in a big chair and be fed chocolates and cigarettes as we talked the talk of old ladies and young boys. Sometimes they bickered lightly, as two people who don't want to be mistaken for each other do. Eventually Alice died, leaving Ella Mae alone and lonely. She moved to a nursing home in Ontario. I wrote her often, managed to visit once before she too came to her end. There wasn't much else I could do.

Especially there was Nellie Barker, my friend for twenty plus years, from my age of six to her death at 90. Always "Miss Barker" to me. Arriving from England in the early part of the twentieth century, she'd worked as a nanny in Montreal. Her employer, an executive with Sun Life Assurance, put part of her wages into that company for her. Out of this she eventually made enough to retire to a little house in the Laurentians. From there for years she rode to market and church by donkey and cart. By the time we met in the 1950s she was living in a wooden house down the mountain from her previous one, its porch looking out across the valley.

My father bought the neighbouring property and as a sign of occupancy mother and sons were plunked down there for several summers, on my part probably too many since it cut me off from what friends I had in my village. Getting us to and from this place was always difficult given how carsick the trips made me. My dad would get more and more frustrated and angry with his puny child as we repeatedly stopped so I could jump out and throw up. As a result, on those occasions my father turned up to take the family home for a while, I was left behind at Miss Barker's. (Who knows how we managed those other long car trips elsewhere as a family.)

Whether staying the week or just dropping by I was at her place often enough and long enough to work my way through shelves of Victorian novels in editions decades old. Terms from these would occasionally find their way into my English essays. Inevitably the teacher would strike them out with angry red pen and a rebuke for making up words.

Miss Barker and I would tend to the garden, sit on the porch with talk and tea. She'd recount memories of a distant past, seeing the Great Eastern in Liverpool harbour in the 1880s for one. Her back was stooped and her vision poor. Unable to make me out, Peter is that you !? she'd call out in welcome when I came up the porch stairs. In my childhood what I wanted to be when I grew up was her.

Eventually she moved to an old age home in Montreal, where I would also visit from time to time. We'd write to each other and someone would read her my letters. While she was still able to write she'd reply in the scrawl that was all her vision and hands would allow. It was the hands of old ladies, of old people, so beautiful with their wrinkles and veins, that I particularly loved. I couldn't wait to grow old.

After she died I destroyed her letters, leaving behind one more past.

Nellie Barker in her garden near Beaven's Lake, Quebec.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

RELIGION

There was also religion.

The Catholic Church did try to make an altar boy of me. Missing all my cues, repeatedly on the wrong altar step, moving the liturgical missal at the wrong time, my first time serving Mass was the last. As adept at creating chaos in church as during cadet drill, the episode would've gone viral if that had been a possibility in the 1960s. Unfortunately religion itself proved more difficult to ditch. Not only had I been raised a devout Catholic, but from the age of eleven or twelve I was also a devotee of masturbation. Not to mention totally queer. This conflict only grew worse with time. I was afraid of going to hell. I was afraid to so much as swear. I was a mess.

My father, born to a Catholic family, gave religion up out of disgust for the Quebec church and its hand in hand with power, i.e. the Duplessis government --- "psalm-singing hypocrites" was his usual description of the clergy. On the other hand my mother was very definitely the Catholic she had been brought up to be and wanted her children the same. Thanks a lot mum . . .

So anyways, religion: I was desperate, it was destroying me. Within a year of leaving home I was rid of it. But I did have to leave to accomplish that.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SCHOOL

In St. Eustache sur le lac, our village of 2-3,000, the Protestants, English-speaking, had much the better facilities and educational system. In comparison the Catholic system in the English/French village was a patched together solution to schooling anglo-Catholics. Up to Grade 7 or 8 we shared a building and a principal with franco-Catholics, the schoolyard itself ending up informally divided. For high school anglo-Catholics were shipped across the river to a regional school of their own. Despite a catchment area extending out at least forty or fifty miles, it could only come up with a couple of hundred students and consisted of an excess of language courses, textbooks that seemed to have been handed down from generation to generation, one good history teacher, one good math teacher (who unfortunately my class didn't have the final year), and little in the way of extra-curriculars.

As for me, being a good if literal boy who believed everything any adult told me, I liked school until the last couple of years and was intelligent enough to get by even at the end. By then I couldn't concentrate any more, couldn't study, was always in conflict with my teachers. Some of them I didn't like, some of them didn't like me, some of them were certifiably deranged. For the most part they passed on to their students a worldview that was an unquestioning regurgitation of what they'd in turn been spoon-fed. Looking back I see myself as a trained seal taught to do tricks for morsels of praise. The experience turned me into a lifelong contrarian.

In terms of being a "literal boy", this was both part of my naivety and to some extent one more survival tactic learned or inherited from my mother -- best listen to the world carefully. It was also a useful form of passive resistance, both in general and with perfectionists like my father -- if you hadn't done what they wanted they should have phrased it with more care, their words your defence. Which is to put all too clever a spin on it, placing agency in my hands where it never was.

THINGS THAT SEEMED BIG AT THE TIME

In any case the following is from that eleventh and final year of school, in a time when eleven years covered what now takes eleven years of high school plus one year of CEGEP.

Our grade 11 history teacher Janet Paul helped me negotiate the script of my apparently unacceptable high school skit with the principal. Notice the inkwells and cartridge pens on the desks, ballpoint was forbidden. In elementary school it had been pen & nib. Classes ran five days a week from 9am to 4pm, with a lunch break of either 3/4 or a full hour. According to the blackboard we had 12 subjects: religion, English literature, English composition, French grammar, French compostion, history, chemistry, physics, Latin poetry, Latin prose, intermediate algebra, and trigonometry. There were several hours of homework per night with double that on weekends.

The class chose me as its representative, basically a go-between in dealing with teachers on those very limited issues the school might regard as open to discussion. Our home room teacher was a Virgin Mary cultist and multiple Virgins stared down from three walls. Did the windows remain image free in hopes the Virgin herself might appear there? My class wanted to put up our own posters like other classes, but she permitted nothing else. Repeated attempts at negotiation lead nowhere: this was a Catholic school after all, with virgins cheering us on from three directions how could we possibly want more? End of story. In response at Christmas I gave her the John Fowles bestseller The Collector, in which an abductor holds the object of their affection in basement captivity. As far as I was concerned it summed up the situation. Held between thumb and finger the volume was returned to me in disgust: scratch my name from her good books. But she got the point and subsequently relented on the virgins.

Next up an ex-military/jock type seemingly assigned at random to teach a subject of which he had no understanding. Classes inevitably ended with him floundering at the blackboard, a picture of confusion and incompetence. It was humiliating and he compensated by giving us twice the homework of any other teacher. Already under a heavy workload it made things even more difficult for students. Which in turn made it possible for him to blame all classroom problems on his assignments not being completed. Everybody was unhappy and I finally complained during class. Angry, he dared me to take it higher and see how that went. As the words were coming out his mouth I got up, walked out, went to the principal. And indeed, see how far that gets you in any Catholic school in the early 1960's. Throw in said principal was a skinny stiff-limbed scarecrow creature who wore shades everywhere, a plastic whistle permanently planted between his lips. At some point there were even rumours about the disappearance of school funds. So now I was in two more bad books.

Strike three: in a school with little extra-curricular activity beyond a small chess club I decided a drama group was called for. My only experience had been at nine or ten performing improv tales with a friend for the younger kids in the neighbourhood. An upturned table our usual stage, her mother's make-up was our path to make believe. Called home to lunch in mid-performance one day I scurried to the bathroom unseen, scraping everything away to avoid an explosion from my father. In desperation at some telltale remainder I cut off my eyebrows. No one noticed.

Now, at sixteen, the water already hot, might as well bring it to a boil. So after recruiting some players I wrote a 20 minute skit for them, a parody of school, teachers, students, mostly a series of poorly scripted inside-jokes based on my own classroom. Of course the principal was having none of it, but with one of the few decent teachers by my side we negotiated. He cut away half the skit and allowed it to be put on in the gym/lunchroom. Not consisting of very much to start with and now only ten minutes long and incoherent, it was performed before a mystified, bored audience. Apparently though there was enough left intact to cause one teacher to burst into tears. The young are cruel and I regret causing pain. The marks against me multiplied exponentially.

Into all this stepped my father. For the first time in his life he'd decided to take an interest in my education and went to a parent-teacher night. Angry as hell at what my teachers told him he returned home threatening to pull me out of school and send me to work. In another first I surprised both of us and laughed in his face, asked him why he cared since I was nothing but a "little bastard", his favoured description of me by this point. He was a hard man not a vindictive one, however he felt about me he would not try to deny me something as essential as a high school certificate. Or so I gambled in this one act of defiance. The next day, having met my father, one of my teachers actually apologized.

Meanwhile on the home front, sometime during those last couple of years he had persuaded my mother that as a boy I was too close to her and she needed to step back. (And what was that really about?) Feeling like a betrayal, this new distance between my mother and me, a matter of degree, resulted in unhappy words on my part that affected our relationship permanently. We bruise as we bounce off each other and school and home were one big tangle of bruises.

The stroke of luck in those final, difficult high school years was despite being a regional school in another village there were a lot of kids in my class with whom I'd grown up. I was very fond of many of them and most of us got along. As a result the influx of strangers that comes with such a school was not a great problem. I wasn't the school queer, wasn't victimized. But undoubtedly more than one student suspected I was a homo, and some may have said nasty things, and once I did have to scrape spit off the back of my coat when I got off the school bus in the afternoon. But not much was overt or widespread, I wasn't on many people's radar. It was more along the lines of a lowering of voices, a sudden silence when I joined certain groups in the schoolyard. These encounters became useful lessons in sidestepping the obvious, the art of appearing not to notice proved a handy tool in dicier future situations. High school: one more source of turmoil I was glad to leave behind.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

When In Doubt Ask Yourself: What Would John Wayne Do?(John Wayne? who's that?)

However different it may or may not be now, certainly back in the 1950s and early '60s boys were expected to confine themselves to what was considered sufficiently masculine, were peer-pressured and heavily policed for how they walked, talked, held their hands, dressed, threw a ball, for their haircuts, their interests, and anything else you care to name. Anyone straying beyond the red line on the sissy-detector risked ridicule and isolation, was highly suspected of being queer, at best was thought weak.

As for those who actually were gay, no matter how hidden, how deep in the closet you were still a queer, faggot, homo, fairy, fruit. Whether or not it was to your face, in one way or another it was always there in your face, the world around you made it difficult not to internalize the message. Religion, school, family, the prevailing culture, there was no refuge within them or from them. There was nothing for a gay kid in a small town.

Seemingly. Decades later I did hear firsthand stories of some boys having sex with other boys in the village and maybe that would have helped and maybe it wouldn't have. You accommodate what you have to. If on the one hand I was increasingly miserable beyond the age of eleven and dealing with more tension and pressure with each passing year, on the other there was an excellent roof over my head, plenty of food on the table, and an education provided, however less than competent. Weigh that out as you will.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

So that's where I was coming from. As far as I remember it and understand it.